Note: If you’re attempting to read this as a Fediverse post, you might find it rather confusing. I recommend using a web browser to read it properly, following this link.

This one was a bitch!

Actually: not so much, if I had read the puzzle properly. More about that further below.

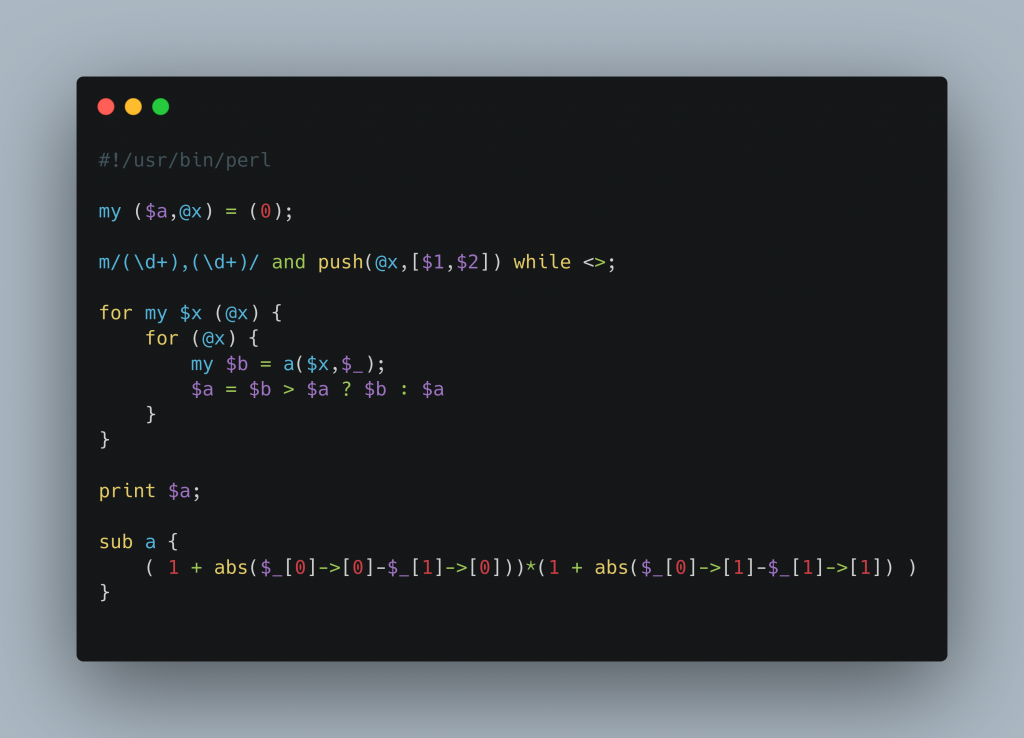

Part 1 was dead easy. Just writing down. I couldn’t finish part 2 in the morning, so I tried again later, being rather confident that I had the right idea.

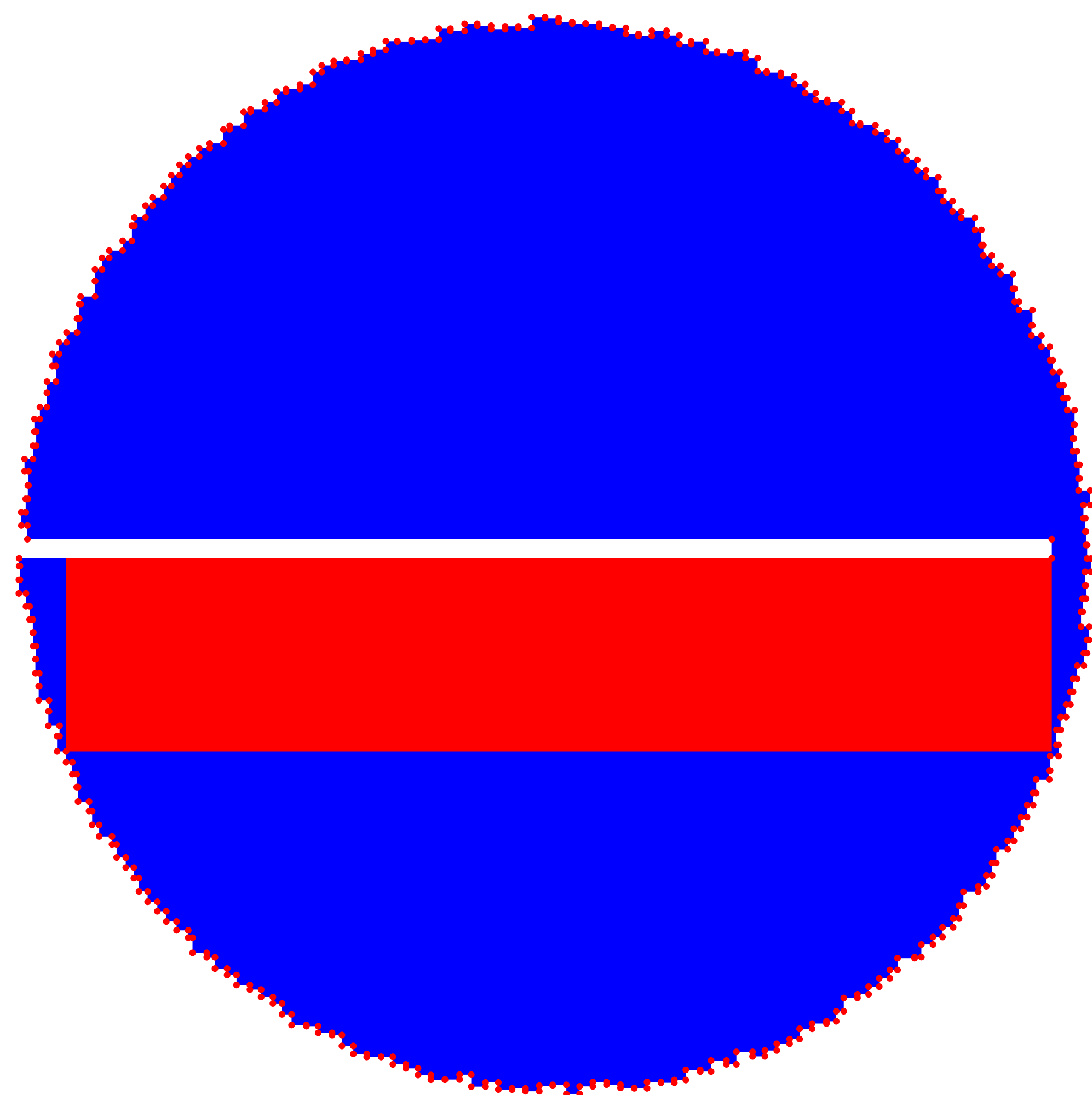

When I started again, the solution worked just fine for the sample, but not for the real data. I couldn’t figure out, what had gone wrong until I plotted the data. Then some errors, more plotting until finally fixing everything. No way, I’m going to finish these year’s puzzles by the evening of the 12th , I reckon.

The challenge

Given was a set of dots in the plain by their coordinates. Asked was the area of the biggest square that could fit in a rectangle between any two of these points, with the sides of the rectangle being parallel to the x and y axis.

The idea

Just store the points in an array, try every combination and calculating the maximum.

The updated challenge

Now we draw horizontal and vertical lines from one point to the other, until all points are connected. The challenge is now the same as in part 1, but so that the entire rectangle is in the inside of the line.

Now: Had I read the challenge properly, namely the part, where it said:

Tiles that are adjacent in your list will always be on either the same row or the same column.

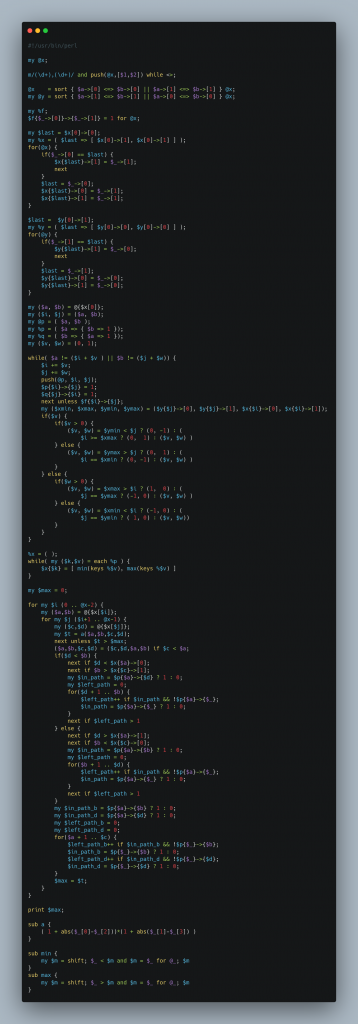

I assumed wrongly that the points were not given in any particular order, and also that there would be a lot of points in the inside, which I would have to ignore. So, more than half of the code is dedicated to find an outline, to encircle a random set of dots.

Half of the time, half of the code, basically for nothing. That’s why there are more than 100 lines of code, which are just useless. I still post it, because this is not about bragging how smart I am, but about the process.

Then I made another mistake: I somehow assumed the outline should be almost convex, but it wasn’t. Like, not at all.

That’s, where the drawing comes in: Thanks to the wonderful SVG vector graphic standard, this was a piece of cake. In the end, it all worked, but it could have been so much easier.

So, this is how you do something wrongly, but still get the answer right.

You may laugh.

Leave a Reply